Spinal Cord Injury Radiology X-rays

Radiological investigations are crucial to medical professionals in determining an accurate diagnosis of spinal injury. Once a patient’s condition is stable, plain x-ray radiographs are generally taken in the hospital radiology department. When symptoms of nerve damage exist a doctor should be in attendance to ensure any spinal movement is kept to a minimum. Sandbags, collars and tapes are not always radiolucent, and clearer radiographs may be obtained if these are removed after preliminary films have been taken. Emergency departments may use mobile radiographic equipment for seriously ill patients, and those unable to be moved, but the quality of these films are usually inferior.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are used for further evaluation. When x-rays prove no fracture, dislocation or other bony abnormalities exist it is important to remember, it does not mean no spinal cord injury exists. A central disc prolapse, ligamentous damage, or cervical spondylosis may have occurred. Common amongst children and the elderly these render a spinal cord vulnerable to further damage, especially in cases of cervical hyperextension injuries.

Cervical Spinal Cord Injury Radiology X-Rays

The most telling and important spinal x-ray when cervical spinal cord injury is suspected the lateral view of the neck obtained with the x-ray beam horizontal consistently offers the best possible insight to spinal damage and can be taken in the hospital emergency department without moving a supine (face up) patient. In a best case scenario lateral and anteroposterior (taken from directly above) x-rays should be thoroughly scrutinized before open mouth views of the odontoid process are taken as the latter normally requires removal of the collar and some adjustment of position.

The initial lateral view x-ray should be repeated if the radiograph does not show the whole of the cervical spine and the upper part of the first thoracic vertebra. Failure to embody this often results in injuries of the lower cervical spine being missed.

Lower cervical vertebrae are generally obscured by the shoulders unless depressed by applying traction to both arms. This traction must be stopped if it produces pain in the neck or exacerbates any neurological symptoms. If the lower cervical spine is still not seen, a supine “swimmer’s” view where the near shoulder is depressed and the arm next to the cassette abducted can show abnormalities as far down as the first or second thoracic vertebra. The interpretation of cervical spine radiographs may pose problems for the inexperienced who overlook the fact a spine consists of bone (visible) and soft tissue (invisible).

Thoracic and Lumbar Spinal Cord Injuries

The thoracic spine is often demonstrated well on the anteroposterior chest radiograph that forms part of the standard series of views requested in major trauma. This x ray may be the first to reveal an injury to the thoracic spine.

Radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine must be specifically requested if a cervical spine injury has been sustained (because of the frequency with which injuries at more than one level coexist) or if signs of thoracic or lumbar trauma are detected when the patient is log rolled. In obtunded patients in whom the thoracic and lumbar spine cannot be evaluated clinically, the radiographs should be obtained routinely during the secondary survey or on admission to hospital. Unstable fractures of the pelvis are often associated with injuries to the lumbar spine.

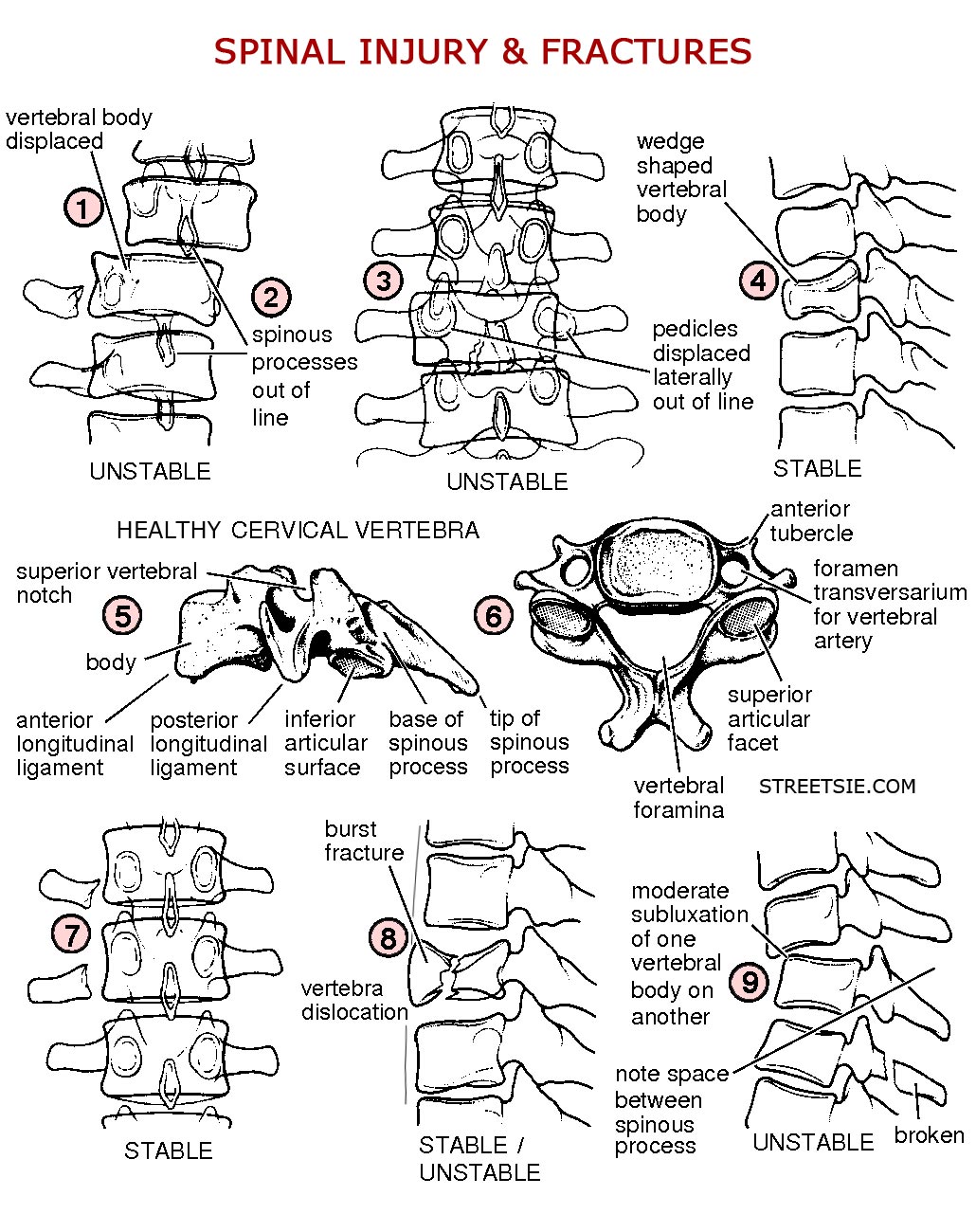

A significant force is normally required to damage the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral segments of the spinal cord, and the skeletal injury is usually evident on the standard anteroposterior and horizontal beam lateral radiographs. Burst fractures (8), and fractures affecting the posterior facet joints or pedicles (3), are unstable and more easily seen on the lateral radiograph. Instability requires at least two of the three columns of the spine to be disrupted. In simple wedge fractures (4), only the anterior column is disrupted and the injury remains stable.

A detailed demonstration of the thoracic spine can be extremely difficult to obtain, particularly in the upper four vertebrae, and CT scans are often required for a clearer definition. Instability in thoracic spinal injuries may also be caused by sternum or bilateral rib fractures as the anterior splinting effect of these structures will be lost.

One particular type of fracture, the “Chance” fracture, is typically found in upper lumbar vertebrae. It runs transversely through the vertebral body and usually results from a shearing force exerted by the lap component of a seat belt during severe deceleration injury. These fractures are often associated with intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries.

Haematoma (blood pooling – bruising) in the posterior mediastinum (rear mid chest cavity region) is often seen around a thoracic fracture site, particularly in the anteroposterior view of the spine and sometimes on the chest radiograph requested in the primary examination. If there is any suspicion that these appearances might be due to traumatic aortic dissection, an arch aortogram will be required.

Reading X-Ray Films Bone and Soft Tissue Damage

In addition to cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral sections a spinal column is divided into three basic column sections; anterior (front), middle, and posterior (back). When deciphering spinal x-rays keep an ABC’S approach in mind as described in ”The ABC of Spinal Cord Injury” (see references).

A – Alignment

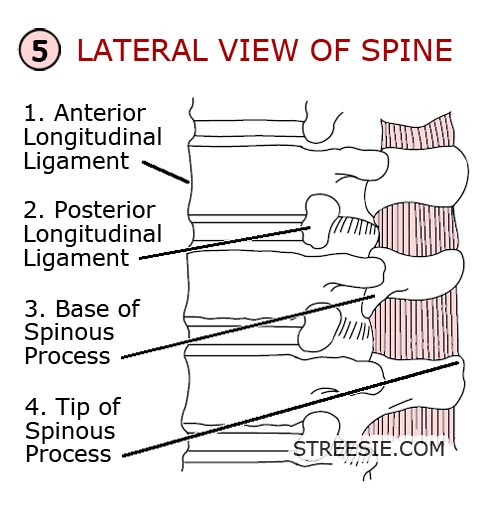

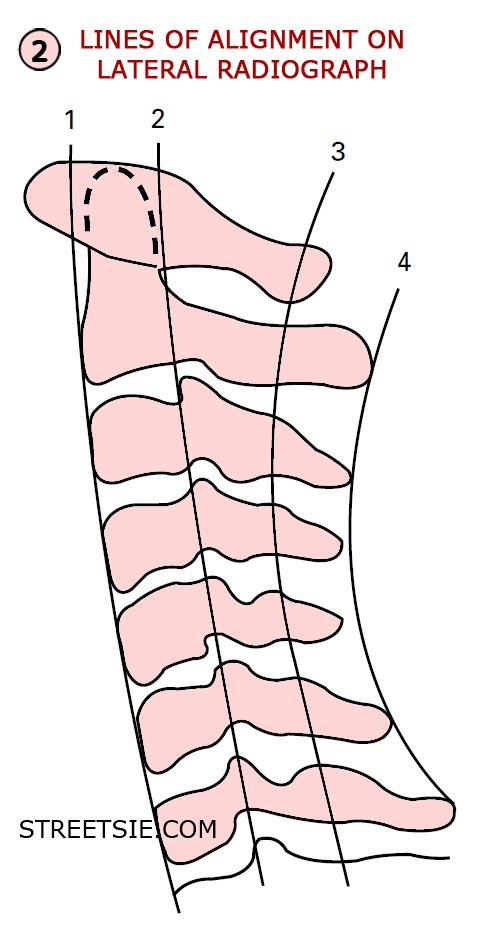

Follow four lines on the lateral x-ray (2) (5);

- 1. The fronts of the vertebral bodies — anterior longitudinal ligament.

- 2. The backs of the vertebral bodies — posterior longitudinal ligament.

- 3. The bases of the spinous processes.

- 4. The tips of the spinous processes.

B – Bone

Follow the outline of each individual vertebra checking for any steps or breaks.

C – Cartilage

Examine the intervertebral discs and facet joints for displacement. The disc space may be widened if the annulus fibrosus (outer wall of disc, comprising numerous layers of organic material crisscrossing each other at angles for structural strength which contain the core of the disc, the nucleus pulposus) is ruptured or narrowed as in degenerative disc disease.

S – Soft Tissue

Check for widening of the soft tissues anterior to the spine on the lateral radiograph, denoting a prevertebral haematoma, and also widening of any bony interspaces indicating ligamentous damage—for instance separation of the spinous processes following damage to the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments posteriorly.

Diagnosing Spinal Cord Injury X-Rays

Any evidence of either anterior or posterior displacement (1) between vertebrae greater than 4mm on a lateral cervical radiograph is considered abnormal. Anterior displacement of less than half the diameter of the vertebral body suggests unilateral facet dislocation, displacement greater than this indicates bilateral facet dislocation. Atlanto-axial subluxation (dislocation) may be identified by an increased gap (of more than 3mm in adults and 5mm in children) between the odontoid process and the anterior arch of the atlas on the lateral radiograph.

On the lateral radiograph, widening of the gap between adjacent spinous processes (9) following rupture of the posterior cervical ligamentous complex denotes an unstable injury which is often associated with vertebral subluxation (9) and a crush or compression fracture of the vertebral body. The retropharyngeal space at C2 should not exceed 7mm in adults or children whereas the retrotracheal space at C6 should not be wider than 22mm in adults or 14mm in children (the retropharyngeal space widens in a crying child).

Fractures of the anteroinferior margin of the vertebral body otherwise known as “teardrop” fractures are often associated with an unstable flexion injury and sometimes retropulsion of the vertebral body or disc material into the spinal canal. Similarly, flakes of bone may be avulsed from the anterosuperior margin of the vertebral body by the anterior longitudinal ligament in severe extension injuries.

On the anteroposterior radiograph, displacement of a spinous process from the midline (2) may be explained by vertebral rotation secondary to unilateral facet dislocation, the spinous process being displaced towards the side of the dislocation. The spine is relatively stable in a unilateral facet dislocation, especially if maintained in extension. With a bilateral facet dislocation, the spinous processes are in line, the spine is always unstable, and the patient therefore requires extreme care when being handled. The anteroposterior cervical radiograph also provides an opportunity to examine the upper thoracic vertebrae and first to third ribs: severe trauma is required to injure these structures.

Oblique radiographs are not routinely obtained, but they to help to confirm the presence of subluxation or dislocation and indicate whether the right or left facets (apophyseal joints), or both, are affected. They may elucidate abnormalities at the cervicothoracic C7-T1 junction and some authorities recommend them as part of a five-view cervical spine series. The 45 degree supine oblique view shows the intervertebral foramina and the facets but a better view for the facets is one taken with the patient log rolled 22.5 degree from the horizontal.

Flexion and extension views of the cervical spine may be taken if the patient has no neurological symptoms or signs and initial radiographs are normal but an unstable (ligamentous) injury is nevertheless suspected from the mechanism of injury, severe pain, or radiological signs of ligamentous injury. To obtain these radiographs, flexion and extension of the whole neck must be performed as far as the patient can tolerate under the supervision of an experienced doctor. Movement must cease if neurological symptoms are precipitated.

CT Scans – Computed Tomography

If there is any doubt about the integrity of the cervical spine on plain radiographs, CT scans should be performed. These provide much greater detail of the bony structures and will show the extent of encroachment on the spinal canal by vertebral displacement or bone fragments. It is particularly useful in assessing the cervicothoracic junction, the upper cervical spine and any suspected fracture or misalignment.

Helical (or spiral) CT scans are now more available. These allow for a faster examination and clearer reconstructed images in the sagittal and coronal planes. Many patients with major trauma will require CT scans of their head, chest or abdomen, and it is often appropriate to scan any suspicious or poorly seen area of the spine at the same time rather than struggle with further plain films.

MRI Scans – Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI gives information about the spinal cord and soft tissues and will reveal the cause of cord compression, whether from bone, prolapsed discs, ligamentous damage, or intraspinal haematomas. It will also show the extent of cord damage and oedema (swelling) which is of some prognostic value. Although an acute traumatic disc prolapse may be associated with bony injury, it can also occur with normal radiographs, and in these patients it is vital that an urgent MRI scan is obtained.

These scans can also be used to demonstrate spinal instability, particularly in the presence of normal radiographs. MRI has superseded myelography, both in the quality of images obtained and in safety for the patient, allowing decisions to be made without the need for invasive imaging modalities. Its use may be limited by its availability and the difficulty in monitoring the acutely injured patient within the scanner.

Pathological changes in the spine — for example, ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis — may predispose to bony damage after relatively minor trauma and in these patients further radiological investigation and imaging must be thorough.

Conclusion

Fractures of the spine are often complex and inadequately shown on plain x-ray films. X-rays of the lower cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine are commonly obstructed by other bones and organs. CT scans display bony detail more accurately. MRI scans best demonstrate the extent of spinal cord and soft tissue damage.

An accurate reading and diagnosis of spinal injuries and subsequent spinal cord injuries through means of x-rays, CT and MRI scans requires specialized training, expertise and experience. Never be afraid to ask for a second opinion when it comes to your spine.

My Personal Experience

Locked in the vice grips of Gardner-Wells tongs staring up at the fluorescent bulbs a doctor came by interrupting my torturous “nose toilet” routine, a nurse fishing for boogers with a cue tip. Almost boasting he proudly held up an x-ray of cervical vertebra 4-5 at right angles to each other. I can’t recall what he said or what condition the patient was in but that image has always stuck in my mind. I guess it did help lessen the shock value of seeing my own x-ray films but such horrendous injuries usually result in death. A macabre trophy to some spinal injury specialists I’m sure. Back then the bedside manner of many doctors and nurses left a lot to be desired.

Locked in the vice grips of Gardner-Wells tongs staring up at the fluorescent bulbs a doctor came by interrupting my torturous “nose toilet” routine, a nurse fishing for boogers with a cue tip. Almost boasting he proudly held up an x-ray of cervical vertebra 4-5 at right angles to each other. I can’t recall what he said or what condition the patient was in but that image has always stuck in my mind. I guess it did help lessen the shock value of seeing my own x-ray films but such horrendous injuries usually result in death. A macabre trophy to some spinal injury specialists I’m sure. Back then the bedside manner of many doctors and nurses left a lot to be desired.

Recently I clean broke my left leg Tibia and Fibula. I didn’t realize turning from my desk the tip of my shoe caught the table leg, it went off like a firecracker. I looked down to see my foot pointing backwards, not good Graham, I thought to myself. My carer and girlfriend sat glaring jaw open silent at the kitchen table. I said, “Oops.” In a very stern voice my girlfriend replied, “What have you done now!”

We splinted my leg with two football socks bandages and a plastic anti-foot drop splint. After a shower seven days later hoisting me back to bed I noticed my lower leg bend. I admitted myself to hospital. They put a full lower leg cast on then cut a two inch gap down the front in order to periodically check for pressure areas. The next morning prepped for surgery they removed the cast outside the surgery doors. When the guy cut the two inch gap he also cut my skin. Unable to operate as the cuts were red and infected they kept me in another 10 days.

Without a spinal unit stuck in the main ward I was constantly surprised how many nurses had no idea how to care for a quadriplegic. One snarled at me, “You should have taken these meds an hour ago.” I said, “Lady, if my hands worked I would have.” They tucked my drain bag and tubing under the mattress with clean sheets, took several hours to figure out that’s why I was sweating. A urologist who clamped off my catheter to take a sample neglected to remove the clamp, sweating again, we discovered it a little faster this time. There were many more errors made but you get the idea, it was not a pleasant stay.

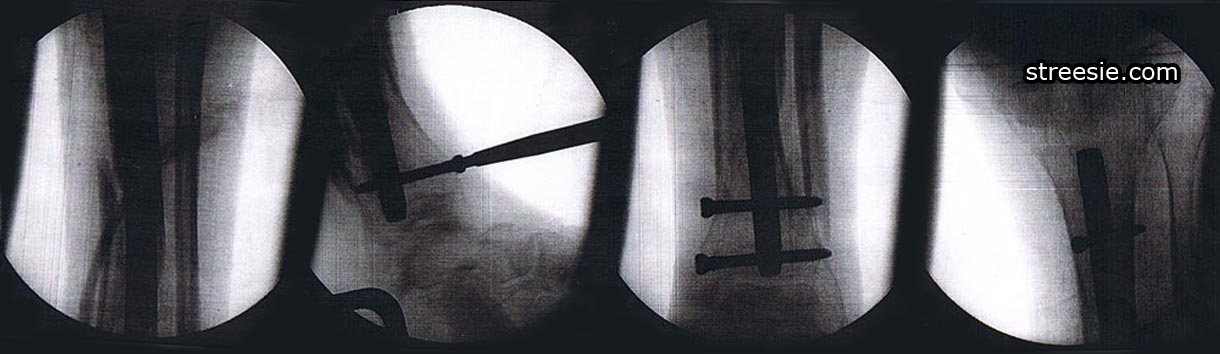

Six weeks post-op I returned for progress radiograph x-ray results. Quite impressed they not only managed to x-ray the correct leg, the clarity and resonance of the x-ray films was excellent. I had the doctor take these photos. You can see the surgical steel rod they call a nail and the screws top and bottom keeping it in place. It was all done through keyhole surgery. Like most images on our website you can click to enlarge.

While I may have strayed from the subject a little with my personal story I want to point out that if you do encounter doctors or nurses, anyone for that matter, who is not aware of your special needs be patient polite and educate them. Your efforts will benefit all of us living with spinal cord injury in the future.

Resources

- David Grundy, Honorary Consultant in Spinal Injuries, The Duke of Cornwall Spinal Treatment Centre, Salisbury District Hospital, UK. Andrew Swain, Clinical Director Emergency Department, MidCentral Health, Palmerston Hospital North, New Zealand: ABC of Spinal Cord Injury: BMJ Books, 2002.

- Gary L. Albrecht. 2006. Encyclopedia of Disability. University of Illinois, Chicago.

Graham,

It sounds like Australian hospitals are similar to American hospitals…except here in America, patients are often presented with a free-of-charge staph infection before checking out. And for extra special patients, MRSA is the going-away present! Good times! Good times!

lol @ Deb; If you enjoy a poke in the eye with a sharp stick there’s nothing like a little Golden Staph Infection to kick start a summer holiday in tropical Fiji or the Cayman Islands, woohoo!

LOL – It’s even more “fun” when you notice the nurses are updating the medical records with the term “staff infection” instead of the correct spelling – STAPH…

It makes me want to start spelling “lawsuit”. Crazy.